Grief had me wide awake at 3 a.m. on Saturday, I was trying to figure out which chores I could cram into the 14 hours before I returned to the land of migraine disability. I had admitted defeat with the ketogenic diet. One more meal was all I had left on the diet; dinner would take me back to migraine as usual.

Grief had me wide awake at 3 a.m. on Saturday, I was trying to figure out which chores I could cram into the 14 hours before I returned to the land of migraine disability. I had admitted defeat with the ketogenic diet. One more meal was all I had left on the diet; dinner would take me back to migraine as usual.

Ketogenic Diet and Hypoglycemia: Cause and Effect

Frustratingly, even though the ketogenic diet reduced my migraine attack severity and enabled me to be more functional, it also caused hypoglycemia—which is in itself a migraine trigger. Despite a month of various fixes, I couldn’t get it under control. (I’ve actually been wrestling with it for two months. That awful nausea I attributed to dehydration was actually hypoglycemia. The wrung out feeling I woke up with each day was the fallout from hypoglycemia-triggered migraine attacks that came on while I slept.)

How I Discovered Hypoglycemia Was the Problem

After increasing to 2500 calories to gain some weight back, I woke up each day ravenous and shaky. This seemed odd—how could I be hungrier than when I ate 1700 calories a day? Knowing that a ketogenic diet could cause hypoglycemia, I began researching. Not only did I discover that it was likely I had hypoglycemia, but the nausea and accompanying symptoms of the previous month fit the pattern of reactive hypoglycemia perfectly.

Reactive Hypoglycemia

Reactive, or postprandial, hypoglycemia occurs two to four hours after eating. It’s usually a crash after eating a meal high in carbohydrates. Although I wasn’t eating many carbohydrates, my blood sugar was so low the rest of the time that I’d crash after my meal each day. It would start two hours after the meal, but I’m so used to ignoring vague physical symptoms that I didn’t notice until they got bad. Which they did like clockwork six hours after eating every night.

Treating Hypoglycemia

The treatment of mild hypoglycemia is relatively easy: eat small, frequent meals and eat a dose of carbs whenever your blood sugar dips too low. The latter was obviously out (it’s hard to dose up with carbs when you are limited to 15 grams a day). The former didn’t work for me either, since I still had a migraine attack every time I ate, so I could eat no more than two meals a day.

Desperately Searching for Fixes

I spent a month trying every possible fix I could imagine: increasing from one to two meals a day, eating the same ratio with less protein and more carbs, a lower ratio, 100 calorie snacks that didn’t seem to trigger migraine attacks (they did, the attacks just built slowly), eating more in the morning, 1 gram doses of sugar, more calories… Nearly everything worked for a day, then became ineffective. I tested my blood sugar so often that my fingertips developed callouses.

Magical Thinking

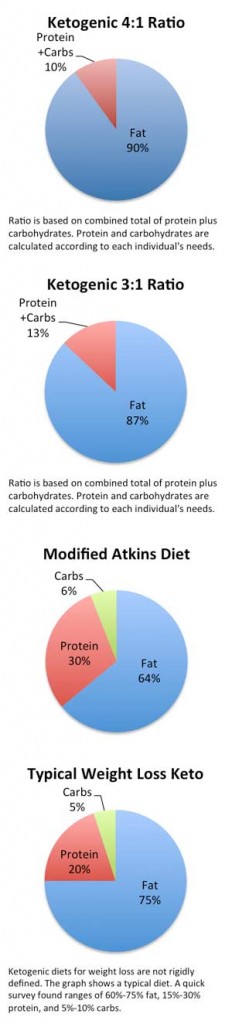

An idea came to mind a couple weeks ago that sounded like pure magical thinking: What if I increasing my ratio to 4:1 (that’s 90% fat) made the diet more effective and enabled me to eat small meals without triggering migraine attacks? I ran it past Hart and my naturopath. They both agreed with the magical thinking hypothesis.

Going for Broke

I didn’t give up on Saturday. I was clinging so desperately to the good hours that I decided to give the 4:1 ratio a shot before calling it quits. I began yesterday by cutting my protein in half so I could keep a relatively high carbohydrate content for the transition period. By evening, I felt remarkably good. I managed three 114 calorie snacks in less than three hours without a migraine attack. A migraine attack didn’t even come on in the night.

Today’s meal plan increased the protein and decreased the carbs some. Four 114 calorie snacks later, no migraine attack ensued and my blood sugar was fine (still on the low end, but manageable). Things went downhill when I ate an actual meal—it triggered a migraine attack and my blood sugar tanked. Several small snacks helped me recover and I’m up and thinking again.

Research Soothes My Worries (a Bit)

Today I learned that a person’s blood sugar range tends to be lower on a ketogenic diet than it normally is. Anything below 70 mg/dL is typically considered hypoglycemic, but 55-75 mg/dL is typical on a 4:1 ketogenic diet. This isn’t a cause for concern as long as the person doesn’t have hypoglycemia symptoms. Also, it can take a full week for one’s blood sugar to stabilize when starting on or changing a ketogenic diet. That means all my dietary tweaks have probably done just the opposite of what I intended. (I am not a medical professional—PLEASE don’t take my word for any of this information. If you’re struggling with a ketogenic diet and hypoglycemia, work with health care professionals to determine the best approach for you. I’m being very careful and consulting with doctors and dietitians as I attempt this unorthodox experiment. Still I worry my low blood sugar is causing long-term harm to my brain. I’m seeing an endocrinologist next week and am going to try get yet another opinion from a neurologist at an epilepsy clinic. Maybe then I’ll find peace of mind.)

Optimism

Obviously, there are a lot of kinks to work out, but I feel like I’m getting closer to getting them sorted. Although most of my earlier fixes didn’t last long, they were all focused on increasing my carbohydrate content. Eating more frequent meals is a far more sustainable option—and one that seems like it could work. I’ve come close to admitting defeat countless times in the last two weeks. I have shed so many tears that I’m distrustful of possible indications of success. But the signs are promising, so I’m still hopeful.

But is the diet helping??? I inadvertently edited out the answer to the question many of you were wondering when I wrote about the ketogenic diet for migraine last week. The answer is a resounding maybe. I have not achieved my primary goals—eating or drinking anything but water still triggers a migraine attack and I still eat only once a day. But small improvements are increasing my quality of life.

But is the diet helping??? I inadvertently edited out the answer to the question many of you were wondering when I wrote about the ketogenic diet for migraine last week. The answer is a resounding maybe. I have not achieved my primary goals—eating or drinking anything but water still triggers a migraine attack and I still eat only once a day. But small improvements are increasing my quality of life.